by Don Gray, March 15, 2022

Every day we face numerous problems to solve. But as we get better at problem solving, our work often brings us new and more challenging problems. The problem with problems is that

Not all problems are created equal.

The problem-solving methods we learned in school used linear techniques and relied on simplifications such as “there is no friction in the system.” The simplifications are false, but without them, the math doesn’t give nice neat answers, and you can’t solve several of them on the class final.

So how do we deal with problems that increase in complexity and uncertainty? We need a framework that helps us identify the kinds of problems we’re dealing with and suggest possible solutions or strategies.

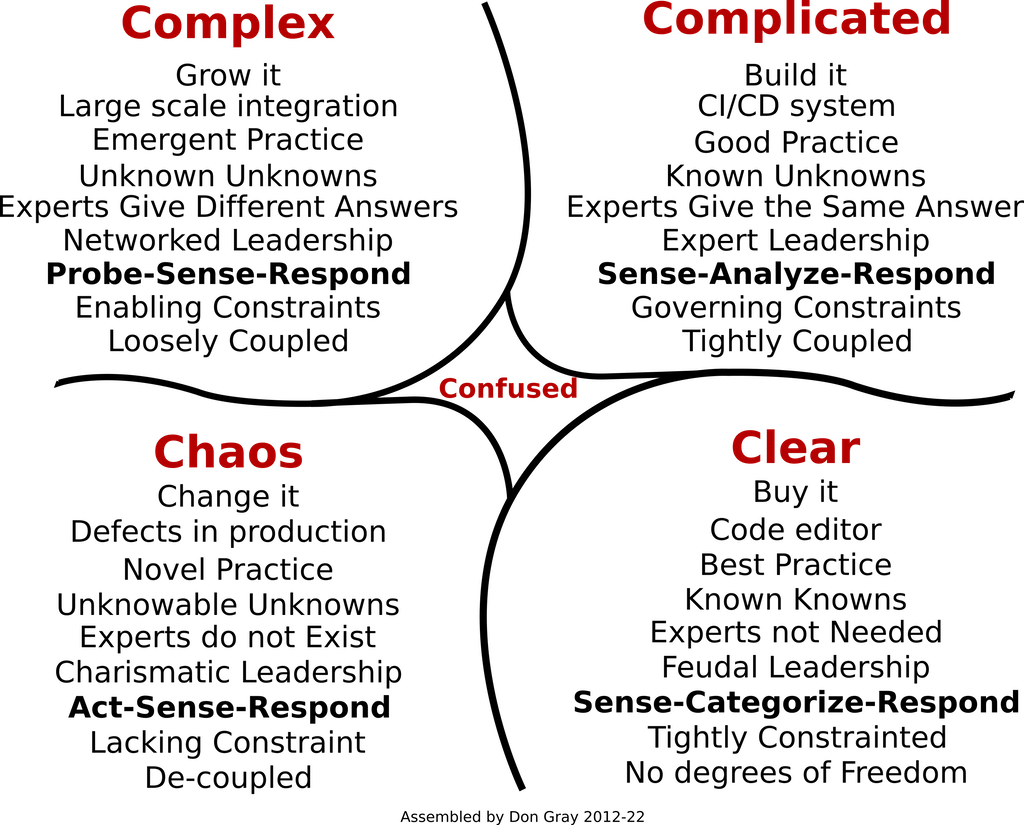

Dave Snowden created the Cynefin® framework that helps us make sense of the problems we face, and provides suggestions on how to approach those problems. The framework is described in the following figure:

I built this diagram over time snagging bits of information, many from Dave Snowden’s blog posts.

Start by asking yourself, “Have I solved this problem before?” If so, welcome to the Clear domain. You know everything needed. The process is tightly constrained. Requirements are common and known to everyone.

“Just Do it.” Or better, buy it if you can. You wouldn’t develop your own editor for coding. Many excellent editors have been around for a very long time: Emacs, vi or VIM work on all major operating systems. Almost every OS comes with a reasonably functional editor such as TextEdit, Notepad, and Nano.

As far as practices go, you have the Best Practice! Well, for you, at this time, for this problem.

If you find a problem you’ve not solved before, but maybe solved something like it, or know of someone who has solved the problem, you’re working in the Complicated domain. You know what you know, and more importantly, you know what you don’t know. You need to find someone to assist you. Or, spend the time analyzing the problem, running some experiments, and learning what you don’t know.

For example, consider CI/CD and build pipelines. The ideas are straightforward, but not always simple to implement. Working on a book with another developer, we noticed differences in our local build systems. The same makefile wouldn’t run on both computers. After flailing around trying to get packages (Ruby/gems) aligned, which didn’t work, we opted for a hosted central build system. We’ve since added other work streams to the build system, so we can focus on the work, and let the build system do its thing.

Here you have Good Practice. Unknowns may vary based on context shifts, changing details, or the technology stack. Be wary of people selling you a Best Practice: you’ll spend a lot of time and money before admitting it doesn’t work for you.

The Clear and Complicated domains exist in the class of Ordered Systems. This means we can directly connect cause and effect. For some reason, humans find comfort in this certainty. Of course, this suggests that Unordered Systems exist.

Systems become Complex when you don’t know what you don’t know. Here there is no clear connection between causes and events. Progress occurs as the result of probing or nudging the system, sensing/observing what happens, and responding.

We can only know how things will turn out at the end. We call this 20/20 hindsight. If you want to sound ostentatious, say “retrospective coherence.” When we start we have a goal, but do not know how to get there. When we get to the goal, we can look back and say “It’s obvious!” Well, now it is.

I once worked on a project with 50+ teams scattered around the globe. Each team worked on their piece, and according to the burn down charts, made good progress—until the day we started trying to connect the pieces together. It won’t surprise you to hear that nothing worked. Important information one team needed could only be provided by the team that just left for the day. And so on, and so forth. Much activity, little progress.

Only when members of each interacting team were collocated did integration make progress. Creating this constraint enabled progress. This became an Emergent Practice.

No system can withstand constant chaos. Chaos sucks energy, obscures the goal, and breaks connections between the parts and leads to death. People run around like their hair is on fire.

In October 2021, Facebook made changes deep in their internet routing tables and all of their websites, Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp disappeared from the internet for about 6 hours. Chaos ensued both for the company and its users—employee key cards did not work, neither did internal email. Everything was gone. Nothing mattered until the BGP entries were corrected and allowed to propagate.

It’s easy to poke at Facebook, but I don’t know anyone who hasn’t done something similar. I have a story from 1986 that shut down part of a factory. Existing practices don’t count. It’s all hands on deck exploring, trying and testing until the problem gets resolved.

We create a Novel Practice using Act-Sense-Respond. While immediately useful, the practice may have no future use as Chaos involves unknowable unknowns, so the next visit to Chaos may involve completely different actions and responses.

So what happens when we mismatch our actions with our domain? The classic example I’ve seen over 35 years occurs thusly:

Manager: We have this new and exciting opportunity for the team! It’s something completely different than anything we’ve done. We need to ship it in 3 months.

Team: Ahh. What?

Manager: Great! It’s settled. Good luck!

[Schedule updates … then just before shipping]

Team: Ahh. Bad luck. We need another 3 months.

I still see variations of this sequence even in “agile” development shops. Hoped for delivery may be expressed as weeks, or sprints, but it still happens.

So what happened? Managers like the comfort of knowing scope, date, and cost. And they’re not bad because of it; all humans desire certainty.

Certainty fits nicely in the Clear domain. The product itself (new, completely different) and developers fit nicely in the Complex domain. The confusion between the relevant domain and actions only becomes apparent when a forcing function (such as shipping) occurs. This throws the team and manager into chaos. Eventually the chaos resolves by shifting the scope, ship date, or moving from Sense-Categorize-Respond to Probe-Sense-Respond actions.

It may look like a crisis, but it’s only the end of an illusion.

Rhonda’s First Revelation - Jerry Weinberg

As I’ve often said:

Problem solving is knowing what to do when you don’t know what to do.

Using the Cynefin framework helps us make sense of our problems giving us more aligned options for solving them and less chance of forcing a solution that has a very low probability of working.

Additional Resources:

How to pronounce Cynefin® and a wonderful introduction video by Dave Snowden

The Cynefin Mini-book

Cynefin for Devs - Liz Keogh

Copyright © 2021-22 Don Gray, The GROWS Method® Institute. All Rights Reserved.

— Don Gray

Follow @growsmethod in the Fediverse, or subscribe to our mailing list:

Sign up for more information on how you can participate and use the GROWS Method®. We will not use your email for any other purpose.